ART113 • Introduction to Aesthetics

Dr. Good’s Beginner’s Guide to Marshall McLuhan’s theory of media and art: How to study media-technologies ecologically? Or, The special role that Artists have in healing the planet

§1. Ecological definition of medium-technology. Technology as an environment.

Media (technology) always must be understood as an extension of the human mind-body. This is a broader definition of a medium than is usually meant, since it applies not just to communication but every technological innovation starting with language. By altering the relationship between our self-system and the environmental systems within which we live, we unintentionally cause changes to both our self and the environment. Because media are extensions of our mind body, We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.

E.g. Clothing extends skin, shoes extend soles of feet, chairs extend the back, automobiles extend legs and stomach, phonetic literacy extends eyes and mind, electric media extend the entire nervous system.

§2. Psychological obstructions to studying media-technologies. The medium is the message.

As extensions of our body-mind, our use of media technologies changes us psychologically and socially. There are two basic reasons why it is very difficult for us to become aware of these changes.

• Rearview-mirror view of the world

The immediate sensory environment – the context within which things are experienced - is itself very difficult to experience because it ‘saturates the whole field of attention so overwhelmingly.’ Perception is always only aware of changes in the field of awareness. Unless the field of awareness is itself changing quickly, it cannot become an object of perception. So we tend to experience the present in terms the prior environment which is visible from the outside.

• Narcissus narcosis, or Auto-amputation

Extensions of the human mind-body result in new relationships between our perceptual and bodily capacities, disrupting our self-system and giving rise to auto-protective measures, i.e. numbness (psychic anaesthesia, emotional dissociation, PTSD. One part of the system is isolated from the other parts in order to protect the whole nervous system. Our use of technologies easily becomes addictive, where we block out the psychic dissonance of the new media environment by absorbing ourselves in sense of control offered by the new technology.

§3. Ecological study of technology requires holism. Pattern recognition vs. classification

Because the environment is not a thing but a changing network of relationships which itself shapes our attention and awareness, there is no technical or specialized study of media ecology. An effective approach must be flexible, creative, not rooted in a particular theory or fixed point of view, and general enough to ‘encompass the entire environmental matrix which is in constant flux.’ Traditionally Artists have been the only people to develop this approach to perceiving ground rather than just figure.

§4. Art as anti-narcotic. Aesthetics is the new ethics.

Technical knowledge cannot solve the problem of numbness since technical knowledge is always about how to do something, not why something should be done or how personal and social identity are unconsciously altered by the use of a technological solution to a problem. So what kind of knowledge can help us avoid cultural narcosis? Only ART can. Art is the ability to overcome perceptual dissonance, not by becoming numb to the dissonance, but by REVEALING it, and therefore discovering a new way to reach a DEEPER LEVEL OF EQUILIBRIUM with the environment. The artist bridges the gap between past and future, reveals the dangers of the new media environment to others, unifies her experience rather than remaining fragmented, studies the distortions of experience created by our OUT-OF-BALANCE RELATIONSHIP WITH NATURE, is the canary in the mineshaft warning us of spiritually-poisonous ways of relating to each other and the world, allows us to accept our experiences for what they truly are, frees our mind. Artists are the only people who actually live in the Present. The technical side of art is the technology of creating effects. The artist can see the present environment because she studies how to reproduce effects of the environment, but in a way that slows down the process to make it perceivable.

§5. Mcluhan’s conceptual toolbox for enhancing pattern recognition. Ideas as probes.

Marshall Mcluhan’s approach is pragmatic, not about explaining technological change but exploring and revealing its unconscious effects on personal and social behavior, experience and self-awareness. His many obwservations can be fit into three basic ways to approach the study of technology: (1) historical studies of the interface between technological innovation and social/psychological change, (2) hot-cool information interface characteristics, and (3) the tetrad form, or the four laws of media.

(a) Environmental history of technology

Looking at the history of technology is a powerful way to see patterns in experience which are otherwise impossible to perceive in the present environment. An overview of western history reveals that societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media with which men communicate than by the content of the communication. Mcluhan’s analysis reveals four basic technological epochs which are defined in terms of the primary vehicle of communication: oral, phonetic-literate, typographic, and electric.

Pre-literate 1.00,000 - 4000 BCE

Phonetic Literate 4000 BCE -1500 CE

Typographic Literacy 1500 - 1950

Post-literacy (retribalized) 1850 - 2010?

People living within these different periods have different experiences of space/time, different sensory balances, different ideas about knowledge, reality, causality, different social,political and economic institutions, and different self-conceptions.

(b) Hot-cool information interface characteristics

All media technologies can be compared with respect to the quality of their interface with the human mind.

HOT medium:

• extends a single sense

• offers high definition (complete filling in of) information

• little completion or active participation by recipient req.

• tends to exclude (sense from awareness, individual from group)

• leads to specialization, fragmentation

• numbs larger awareness, lessens total perception

• short, intense experiences

• tends to hijack attention

COOL medium:

• extends multiple senses

• offers low definition (incomplete filling in of) information

• requires high participation, active completion

• tends to include/integrate information and individuals into communities)

• leads to generalization, consolidation

• engages background awareness

• longer, sustained experiences

Note 1: The temperature of a medium is relative to the comparison and the terms are not meant as categories but as tools of comparison.

Note 2: Since every medium, with the possible exception of human awareness or consciousness, takes another medium for its content, one must be careful to distinguish the interface medium from the content medium when determining the temperature of the interface.

(c) Four ecological laws of media.

The environmental effects of technological innovations can be classified according to four laws of media which articulate four aspects involved in technological change. Normally, we only think of the first two categories of change.

• ENHANCE: What does the new medium improve or enhance, make possible or accelerate

• OBSOLESCE: What is pushed aside or obsolesced by the new medium?

• RETRIEVE: What earlier action or service is brought back into play by the new form? What older,

previously obsolesced ground is brought back and becomes an essential part of the new form?

• REVERSE: When pushed to its limits, of its potential, the new form will reverse what was its original characteristics. What is the potential reversal of the new form?

E.g.

Automobile: enhance speed, obsolesces horse and buggy, retrieves nomadism, reverses into gridlock.

Cellphone: enhances voice, obsolesces phone booth, retrieves childhood yelling, reverses freedom into being a leash.

Capitalism: enhances liberty (of trade), obsoleses community responsibility, retrieves hunter-gatherer patterns, reverses abundance into starvation-scarcity.

§6. Themes from the environmental history of technology

(a) Visuality, literacy and detribalization •

Many of our modernist assumptions, regarding either the neutrality or the intrinsic goodness of technological development, have obscured the cultural sacrifice we made in leaving oral-tribal society, which had established a balance with the environment, a harmonious internal balance of sensory experiences, a stable economic and political order, a deeply immersive involvement in the world. Literacy and symbolic consciousness generally, spreads our awareness past the present into the past and future, and into abstract possibilities which empowers us while at the same time impoverishing and dimming down the fullness of our experience. Literacy extends vision into a master sense, leading to the detached, linear, systematizing mentality of rationalism. Vision can touc h without being touched.

(b) Civilization has been a process of imbalance, ecological Instability, system slippage •

Depression, mental illnesses, apathy, drug addictions and other compulsive-obsessive behaviors occur in ‘civilized’ or ‘modern’ societies, i.e. societies suffering from a continuous process of uncontrolled explosion/implosion, creating perpetual disequilibrium and stress from constant perceptual dissonance. Some technologies that are involved with our current civilizational disequilibrium with the world: phonetic literacy and typography, automobiles, paper/digital currency system, electricity, internet, totalitarian agriculture, certain ideas about: development, what it means to be human, to be happy, to be in control, to be alive. The ills of technology have nothing to do with it being unnatural, but with its introducing perpetual disequilibrium into a process which strives for equilibrium or BALANCE. Is there a way out of this pattern?

(c) Electric culture, space-time compaction and retribalization

Electric media do not merely extend one sense, they extend the entire nervous system, therefore extending self-awareness or consciousness past the body-defined self. The virtually instantaneous effect of electricity speeds up the form of every technology, leading to the establishment of a truly global consciousness (noosphere). We are now faced with trying to understand the infinite ramifications of INFORMATION SOCIETY while we still have time to effect its development. A key tension concerns the differences between the SELF as a disembodied, placeless cyberanimal which simply processes information and the self as a living being connected, and needing to be connected to a place and a time.

(d) Ethics of technology: comfort versus joy

Ignorance is not blissful, it is at best comfortable. True bliss requires optimal experience: i.e. a balance between being challenged and being in control. Technology presents us with a basic problem: how do we avoid narcissus narcosis in the use of new technologies?

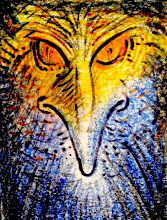

Image above by Daniel Buttrey